2024 Everest Climbing Season Weather

By Michael FaginMt. Everest WeatherWeather patterns for any climbing season are always a hot topic of conversation and one of the keys to a successful climb. Of course, there are many questions. Are extended outlooks/forecasts reliable? Which websites can I trust? Which forecast models are the best? How is climate change impacting weather patterns? Let me briefly go over these items.

El Niño and La Niña

There are general seasonal patterns, or weather tendencies, that occur when we have El Niño or La Niña. We have been in a strong El Niño since last summer. This basically means that sea surface temperatures off the equatorial waters of South America are above normal. For the Himalayan region, this pattern generally delays the start of the summer monsoon season and brings below-normal precipitation and above-normal temperatures.

What happened in 2023? Precipitation during the 2023 monsoon season was slightly below normal. The weather station on Mount Everest has precipitation data only since 2020, but there were some trends. It is interesting that precipitation for 2023 was 29% lower than the totals from 2021, a La Niña year, which is consistent with the general patterns. Finally, Nepal’s temperatures for the first ten months of 2023 were the warmest seen in 13 years and the second warmest in 42 years. Precipitation for Nepal for the first ten months of 2023 was slightly below normal. In summary, these patterns are consistent with El Niño.

Snowpack is the bigger question for climbers. How did the above-normal temperatures and below-normal precipitation from 2023 impact the snowpack? Some of the data from 2023 would suggest below-normal snowpack. However, no data is readily available for the beginning of 2024, although we usually do not get much precipitation early in the year.

El Niño and La Niña 2024

Record Breaking Temperatures are expected, especially for much of Southeast Asia, from July 2023 to June 2024. This is the headline from an article recently published. However, I think this was more applicable to 2023. El Niño conditions are currently weakening.

In fact, starting later in May or June, we will slowly transition to a La Niña phase, so if there are any impacts, they will occur later in 2024. Thus, we are not expecting the El Niño or La Niña to impact the Everest spring climbing season.

La Niña is below normal sea surface temperatures off the equatorial waters of South America. This type of pattern generally brings increased summer monsoonal precipitation for Asia. Also, this pattern tends to increase the chance of severe cyclones in the Bay of Bengal. Again, as I mentioned, we are not expecting any impacts from this pattern till late this summer at the earliest, more likely fall and beyond.

One final word on El Niño or La Niña patterns and the resultant weather outlooks. Any extended outlook going beyond 30 days is subject to the possibility of big errors.

Forecast Models- Which One Is The Best?

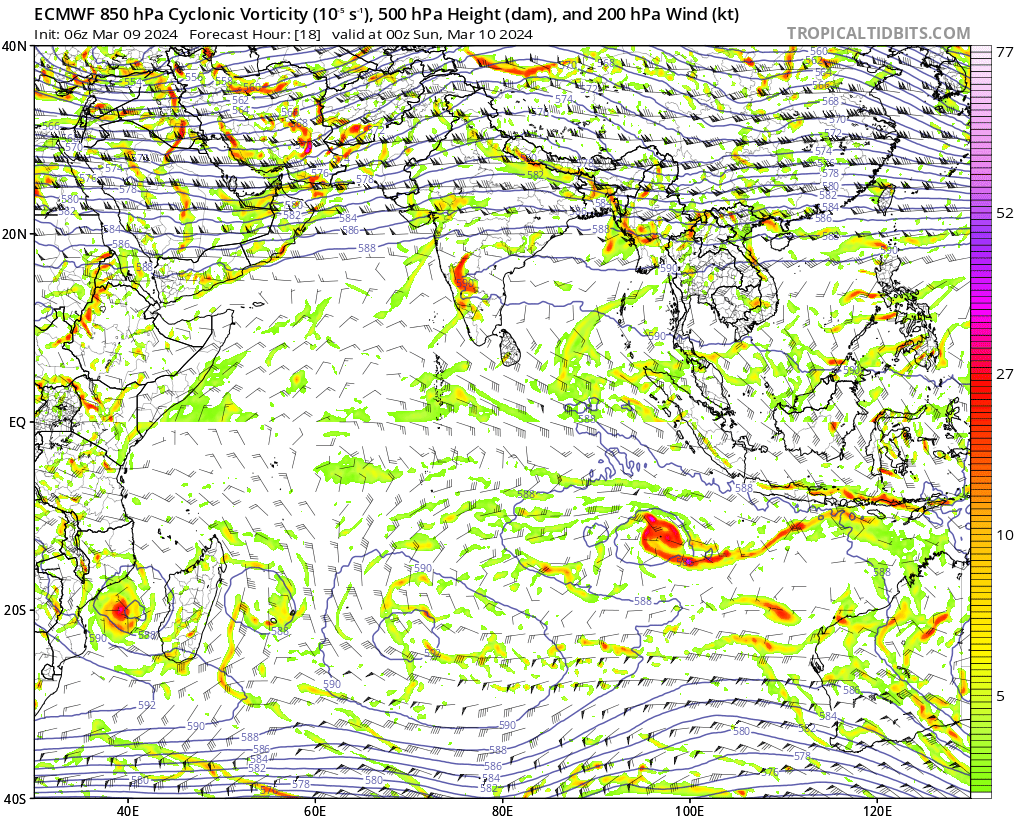

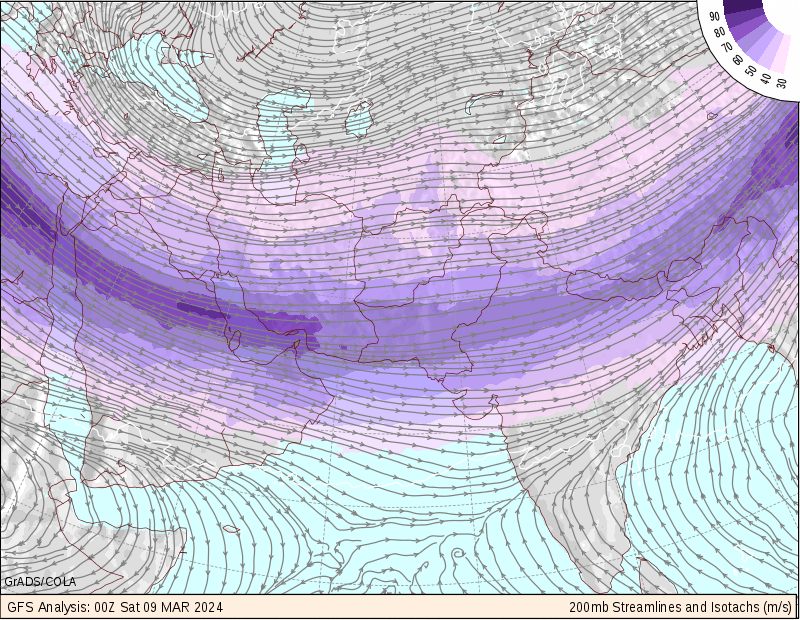

It is always difficult to say which model might “always be accurate!” As a generalization, I find that European forecast model (ECMWF) tends to be the most accurate for the summit winds. The US GFS model generally tend to underforecast the summit winds

Regarding precipitation, both the European and the US models tend to be inaccurate beyond 24 to 36 hours. The UK model tend to be more accurate, but generally, they are only available with a subscription.

The Joint Typhoon Warning Center is a good source for big storms moving in from the Bay of Bengal. However, they usually do not give much advance notice, and most models under-predict the precipitation.

Some websites incorporate the various forecast models and produce forecasts for Mt Everest. I have heard people use these sources, and please note that I do not have an opinion regarding them. Snow Forecast.Com, Mountain Forecast.Com, and Meteoblue are just a few of what is available. And again, I am not passing judgment on these or the ones I have omitted.

Climate Change

This could make a long separate article. In fact, I wrote a piece several years ago.

The retreating glaciers in the Himalayas and the Karakorum have been well documented. This brief YouTube video highlights the significant retreating of the South Col Glacier on Everest. The retreating glaciers and warming climate definitely present climbing challenges. This recent article and this article from several years ago have several mountaineers weighing in on this topic.

How has climate change impacted the weather patterns and forecasting for Mt. Everest? I am often asked this question. I have been forecasting for Mt. Everest since 2003. I have not gone through the process of analyzing any trends, and frankly, I do not see any trend. Over the last 21 years, each spring climbing season seems to have its unique signature.

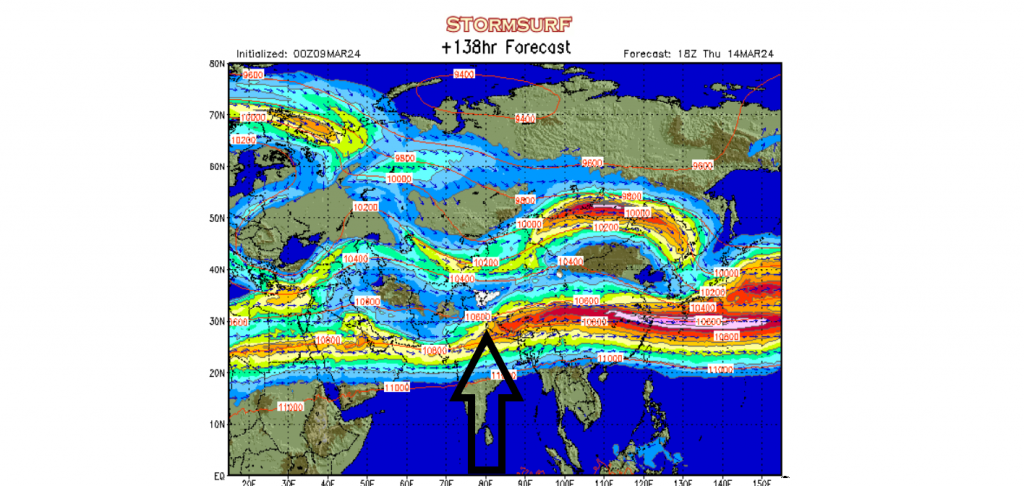

In some seasons, the jet stream seems anchored over Mt. Everest for much of May, providing very limited climbing days. The 2022 climbing season was very unusual, with the jet stream located far from Everest during May. Alan Arnette had a great quote while summarizing 2022: “For the month of May, the jet stream was on vacation.” Will this be a trend? Some meteorologists suggest the jet stream can be greatly altered by climate change. This could be the case, but others, including myself, say, let’s get more data.

Remember the 2021 climbing season? That year, there were two cyclones in May, making it a very difficult season. Will this be a trend? It’s too early to tell.

Final Comments on the 2024 Season

The big driver is the location of the subtropical jet stream (located at 20 to 30 degrees latitude). During March, April, and the early part of May, the jet stream is usually aimed at or close to the Mt. Everest area. Then, usually by the middle of May, the jet stream winds are lower, or shift to the north. This pattern is what climbers like to see for the summit window. We will see what happens during this season. There are times during El Niño that this subtropical jet stream is stronger. We will see what transpires while El Niño weakens this spring.

Prepared by Meteorologist Michael Fagin, Everest Weather